Slab Fork, West Virginia, is a town of 202 people. There’s a handful of houses scattered along a trickling tributary to the Mississippi River, and that’s about it. Naturally, there’s not a lot of money to be made in this humble, isolated community, especially as a soul singer. So, a young Bill Withers, fresh from his service in the army, sold just about everything he owned, collected the $250 that afforded him, and headed off to Los Angeles.

Five long years of very little attention awaited him. He got a job in a factory making parts for aeroplanes that he seemed fated never to fly on and gigged in the evenings. Finally, in 1970, Sussex Records figured they’d give him a shot and assigned the esteemed Booker T to produce his tracks in a hurry and see if they flourished at all in the floundering soul charts. Downbeat by his experiences to date, Withers hardly entered the studio with a lot of faith that stardom awaited him.

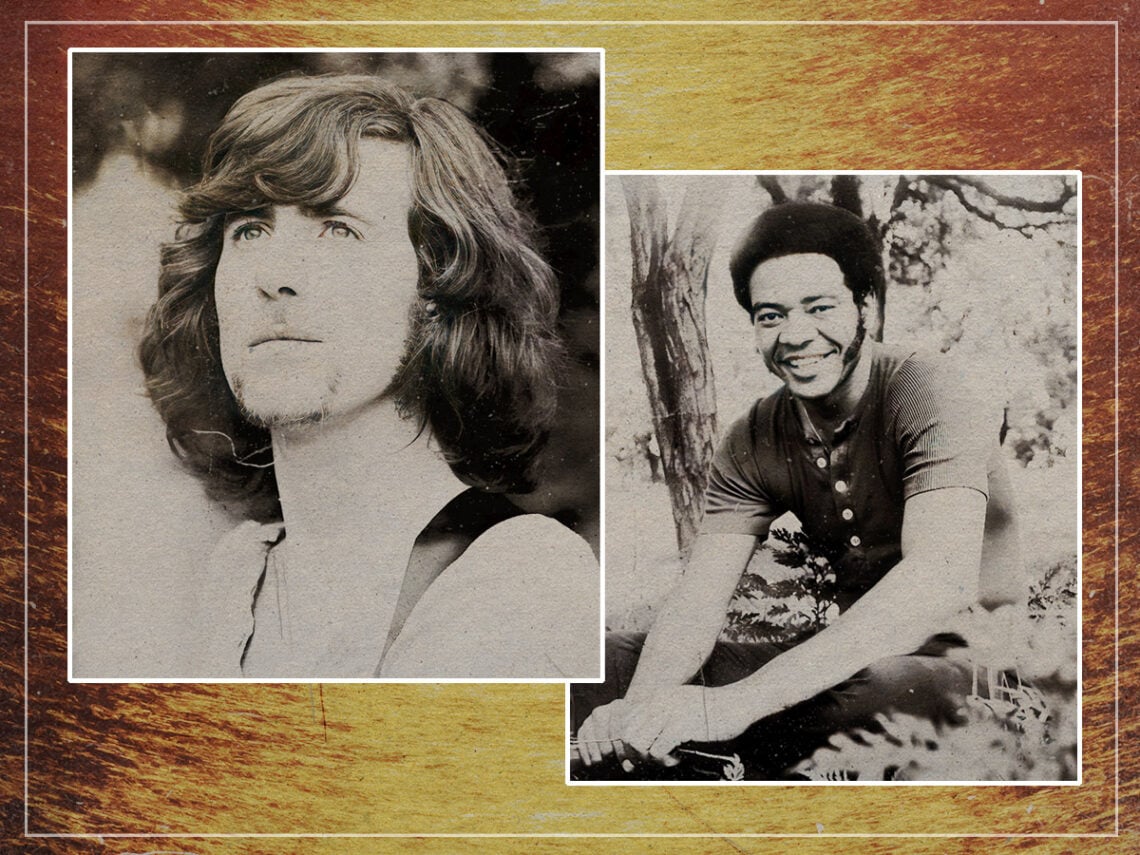

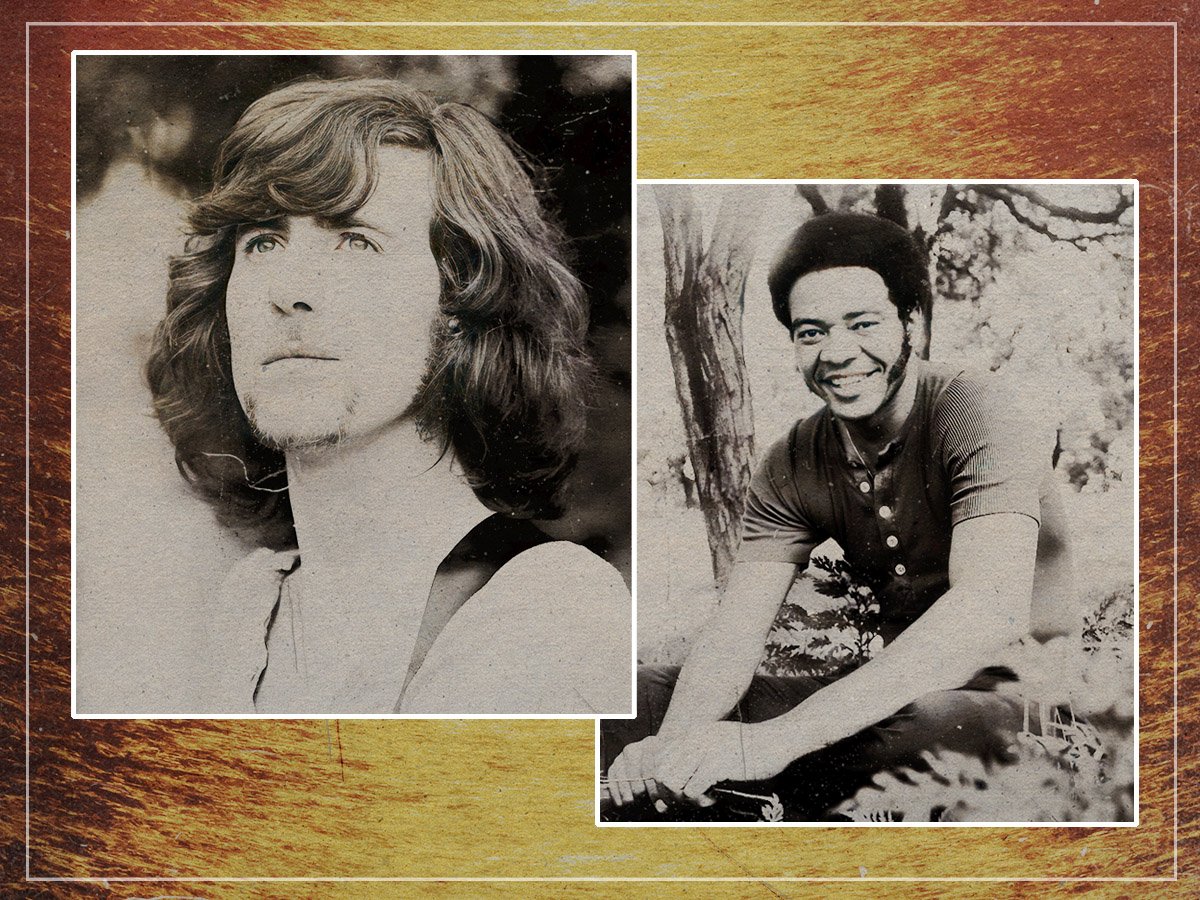

And so, he humbly strummed away in an empty studio room, just about bothering to hone his work before Booker T emerged to hit record. Little did he know that a folk legend was eavesdropping inquisitively from outside an open window. “I was in the studio where we cut the first CSN record – it’s on the corner of Selma and Cahuenga Boulevard in Los Angeles,” Graham Nash recalled.

“I was taking a break, probably smoking a joint outside, and I heard this music coming from one of the other studios,” he told Songfacts. “I was curious, and I walked in. And there was this African American with a guitar, sitting on a chair, with his foot on a box. That was the rhythm he was creating.” Nash watched on, a superstar of the era reduced to a fly on the wall for a passing moment, as Withers finished his song, barely aware that another presence was floating on the periphery.

“He finished the song,” Nash continued, “And I said, ‘Who are you, man? That’s a fantastic song! What’s going on in your life?’ And he says, ‘Well, I’m kind of giving up. I can’t seem to break through. Nobody seems interested. Maybe I’ll just give up.’ And I said, ‘Wait a second. I don’t know who the f–k you are, but you cannot give up. What you have is an incredible gift. You should recognise that and get on with it.’ And he loved that.”

Indeed, he did. However, you suspect he preferred what happened next. The song in question had been ‘Ain’t No Sunshine‘, and Nash had liked it so much that he endeavoured to help Withers bring it to fruition. In fact, he helped to such an extent that the mere act of the arsenal he assembled around the factory worker had a huge bearing on the final song. Withers’ track was incomplete prior to recording; he sang ‘I know, I know, I know…’ as a placeholder, hoping to come up with a verse on a whim in the studio. But as he rattled it off, Booker T and the other esteemed gentlemen present thought it brought an interesting dynamic to the track.

Withers, an artist who had felt frozen out for so long, decided to embrace collaboration and went with the consensus, perhaps an easier decision when you learn about the talent who constituted that opinion. “It was an interesting thing because I’ve got all these guys that were already established, and I was working in the factory at the time,” Withers explained.

Continuing, he added: “Graham Nash was sitting right in front of me, just offering his support. Stephen Stills was playing and there was Booker T. and Al Jackson and Donald Dunn – all of the MGs except Steve Cropper. They were all these people with all this experience and all these reputations, and I was this factory worker just sort of puttering around. So when their general feeling was, ‘Leave it like that,’ I left it like that.” Now, he was not only buoyed by the experience and the encouragement he received, but he also had a hit in his pocket, and the rest is ancient history.

However, the beauty of Withers is that he never truly left that factory and the humility that came with it behind. His songs were forever humanised by that motif of an everyday man keeping the beat himself as he strummed what, in essence, was a folk song, hoping that an open window to the main chance could transfigure it with a bit of soulful dreaminess and, thankfully, he was brimming with the talent to fulfil that, and happy enough to let others masters help him the exultant heights his tracks so often did.

0 Comments